Sep

5

First Nations' Foot “Print”

Sep 2010

By Doreen Marion Gee

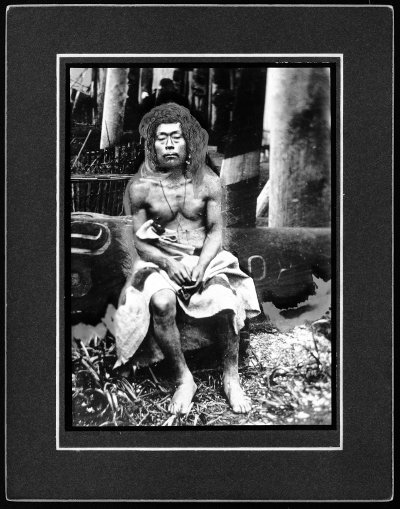

Photos courtesy Royal BC Museaum

The first people to walk on the sands of our shores left a powerful footprint in history. First Nations' history is rich and colourful. Reading about their lives is interesting but seeing it in photographs is downright fascinating. Dan Savard's new book Images from the Likeness House is a beautiful compilation of photos of First Nations peoples and their cultures from as far back as 1857. It is a journey back in time with picture windows into a different world. The reader is there with the elders in a gently swaying canoe under moonlight, or watching expert basket weavers and smelling the smoke of ancient ceremonies. The author lets the reader decide about the objectivity of photographs taken by "outsiders" who shot their subjects according to their own mindset. Savard's work juxtaposes First Nations' history with the history of the art of photography, The origins of a proud people and the origins of an art form weave together into a stunning tapestry of rare glimpses into our West Coast past.

A senior collections manager of the Anthropology Audio Visual Collection at the Royal B.C. Museum, Savard got much of the material for his book from the massive 25,000 photo collection under his watchful eye. His goal in writing the book was to make these treasures available to all. These still photos resurrect the lives of First Peoples of British Columbia and their cultural counterparts in northwestern Washington and southeastern Alaska. The time frame is 1857 to 1920 when photography was in its infancy. On a cold day in 1889, Tsimshian Chief Arthur Wellington Clah went to Maynards' Photography Studio in Victoria to have his photo taken. "Rebekah ask if I going likeness house" he wrote in his diary, "So I go, to give myself likeness. Rebekah stand longside me." Hence the book title.

Savard has a special reverence for the photographs in his book: "In this book, images trump words." He starts with his spectacular photos and only uses text as an afterthought. The writing project brought out his inner sleuth. He wonders aloud why Charles Newcombe photographed the inside of a canoe in 1913. Scrutiny of the photo revealed that the artist was documenting First Nations technology : How to repair a crack in a canoe. "I had a photograph. I needed to determine why it was taken"defines Savard's artistic mission. The images in the book are the real deal. With one exception, they have not been digitally enhanced and are in their raw imperfect state. I was spellbound by the clarity and beauty of these ancient snapshots that could rival any modern digital pic. The photos are mesmerizing. An1898 shot shows a Secwepemc woman preparing a hide in a desolate Kamloops landscape. Another shows a man balancing a canoe paddle in his mouth in a 1896 picture taken at Nootka Sound.

The theme of Savard's book is the interaction between the medium of photography and First Peoples. Most of the snapshots from that era presently in museums were taken by people with scant knowledge of their subjects' culture. But Savard believes their value and importance remain intact. One of the greatest joys for the author is making those crucial connections between photos. For instance, he shows two photos from different photographers capturing the same potlatch event on December 23, 1904, in Alaska. Savard was thrilled with the two totally different perspectives on a sacred cultural tradition.

Equally captivating is Savard's account of the history of photography. I could not put the book down as I read about the early trials of artists lugging heavy glass equipment through the wilds of BC back country. Savard tells an engrossing tale of the early forms of photography, how the craft evolved up until 1920 and the important transition from an elitist art form to a mainstream pleasure.

The book is a cornucopia for history and photography buffs. Amongst other gems, there are chapters on Victoria's early thriving photography business, survey photography, famous photographers of native culture, missionary and First Nations photographers, and the people whose faces were immortalized in print. Maybe you can solve the mystery of Tyee Jim.

I've given only a small taste of the delicious cocktail created by Savard about the First Nations' footprint on history and the people who recorded it with a click and a flash. Get the book and savour more.